Section 1.4 Observational studies and sampling strategies

OpenIntro: Observational Studies and Sampling Strategies video

Subsection 1.4.1 Observational studies

Generally, data in observational studies are collected only by monitoring what occurs, while experiments require the primary explanatory variable in a study be assigned for each subject by the researchers.

Making causal conclusions based on experiments is often reasonable. However, making the same causal conclusions based on observational data is treacherous and is not recommended. Observational studies are generally only sufficient to show associations.

Suppose an observational study tracked sunscreen use and skin cancer, and it was found people who use sunscreen are more likely to get skin cancer than people who do not use sunscreen. Does this mean sunscreen causes skin cancer? 1 No. See the paragraph following the exercise for an explanation.

Some previous research tells us that using sunscreen actually reduces skin cancer risk, so maybe there is another variable that can explain this hypothetical association between sunscreen usage and skin cancer. One important piece of information that is absent is sun exposure. Sun exposure is what is called a confounding variable (also called a lurking variable, confounding factor, or a confounder).

Confounding variable

A confounding variable is a variable that is associated with both the explanatory and response variables. Because of the confounding variable's association with both variables, we do not know if the response is due to the explanatory variable or due to the confounding variable.

Sun exposure is a confounding factor because it is associated with both the use of sunscreen and the development of skin cancer. People who are out in the sun all day are more likely to use sunscreen, and people who are out in the sun all day are more likely to get skin cancer. Research shows us the development of skin cancer is due to the sun exposure. The variables of sunscreen usage and sun exposure are confounded, and without this research, we would have no way of knowing which one was the true cause of skin cancer.

Example 1.4.3

In a study that followed 1,169 non-diabetic men and women who had been hospitalized for a first heart attack, the people that reported eating chocolate had increased survival rate over the next 8 years than those that reported not eating chocolate. 2 Janszky et al. 2009. Chocolate consumption and mortality following a first acute myocardial infarction: the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program. Journal of Internal Medicine 266:3, p248-257. Also, those who ate more chocolate also tended to live longer on average. The researched controlled for several confounding factors, such as age, physical activity, smoking, and many other factors. Can we conclude that the consumption of chocolate caused the people to live longer?

This is an observational study, not a controlled randomized experiment. Even though the researchers controlled for many possible variables, there may still be other confounding factors. (Can you think of any that weren't mentioned?) While it is possible that the chocolate had an effect, this study cannot prove that chocolate increased the survival rate of patients.

Example 1.4.4

The authors who conducted the study did warn in the article that additional studies would be necessary to determine whether the correlation between chocolate consumption and survival translates to any causal relationship. That is, they acknowledged that there may be confounding factors. One possible confounding factor not considered was mental health. In context, explain what it would mean for mental health to be a confounding factor in this study.

Mental health would be a confounding factor if, for example, people with better mental health tended to eat more chocolate, and those with better mental health also were less likely to die within the 8 year study period. Notice that if better mental health were not associated with eating more chocolate, it would not be considered a confounding factor since it wouldn't explain the observed associated between eating chocolate and having a better survival rate. If better mental health were associated only with eating chocolate and not with a better survival rate, then it would also not be confounding for the same reason. Only if a variable that is associated with both the explanatory variable of interest (chocolate) and the outcome variable in the study (survival during the 8 year study period) can it be considered a confounding factor.

While one method to justify making causal conclusions from observational studies is to exhaust the search for confounding variables, there is no guarantee that all confounding variables can be examined or measured.

In the same way, the county data set is an observational study with confounding variables, and its data cannot be used to make causal conclusions.

Guided Practice 1.4.5

Figure 1.2.13 shows a negative association between the homeownership rate and the percentage of multi-unit structures in a county. However, it is unreasonable to conclude that there is a causal relationship between the two variables. Suggest one or more other variables that might explain the relationship visible in Figure 1.2.13. 3 Answers will vary. Population density may be important. If a county is very dense, then this may require a larger fraction of residents to live in multi-unit structures. Additionally, the high density may contribute to increases in property value, making homeownership infeasible for many residents.

Observational studies come in two forms: prospective and retrospective studies. A prospective study identifies individuals and collects information as events unfold. For instance, medical researchers may identify and follow a group of similar individuals over many years to assess the possible influences of behavior on cancer risk. One example of such a study is The Nurses' Health Study, started in 1976 and expanded in 1989. 4 www.channing.harvard.edu/nhs This prospective study recruits registered nurses and then collects data from them using questionnaires. Retrospective studies collect data after events have taken place, e.g. researchers may review past events in medical records. Some data sets, such as county, may contain both prospectively- and retrospectively-collected variables. Local governments prospectively collect some variables as events unfolded (e.g. retails sales) while the federal government retrospectively collected others during the 2010 census (e.g. county population counts).

Subsection 1.4.2 Sampling from a population

We might try to estimate the time to graduation for Duke undergraduates in the last 5 years by collecting a sample of students. All graduates in the last 5 years represent the population, and graduates who are selected for review are collectively called the sample. In general, we always seek to randomly select a sample from a population. The most basic type of random selection is equivalent to how raffles are conducted. For example, in selecting graduates, we could write each graduate's name on a raffle ticket and draw 100 tickets. The selected names would represent a random sample of 100 graduates.

Why pick a sample randomly? Why not just pick a sample by hand? Consider the following scenario.

Example 1.4.7

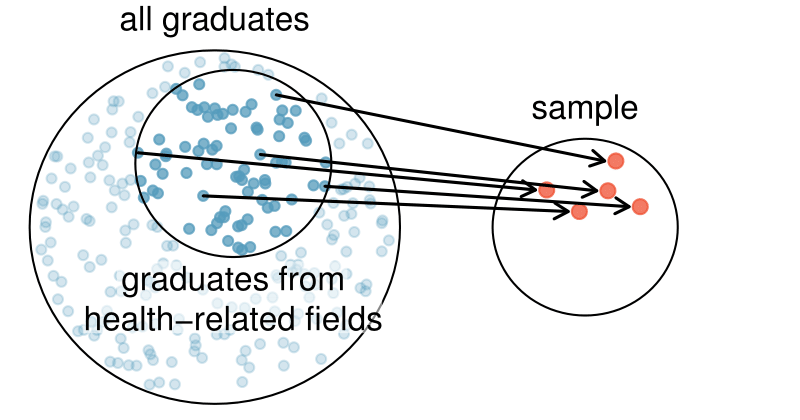

Suppose we ask a student who happens to be majoring in nutrition to select several graduates for the study. What kind of students do you think she might collect? Do you think her sample would be representative of all graduates?

Perhaps she would pick a disproportionate number of graduates from health-related fields. Or perhaps her selection would be well-representative of the population. When selecting samples by hand, we run the risk of picking a biased sample, even if that bias is unintentional or difficult to discern.

If the student majoring in nutrition picked a disproportionate number of graduates from health-related fields, this would introduce selection bias into the sample. Selection bias occurs when some individuals of the population are inherently more likely to be included in the sample than others. In the example, this bias creates a problem because a degree in health-related fields might take more or less time to complete than a degree in other fields. Suppose that it takes longer. Since graduates from health-related fields would be more likely to be in the sample, the selection bias would cause her to overestimate the parameter.

Sampling randomly resolves the problem of selection bias. The most basic random sample is called a simple random sample, which is equivalent to using a raffle to select cases. This means that each case in the population has an equal chance of being included and there is no implied connection between the cases in the sample.

A common downfall is a convenience sample, where individuals who are easily accessible are more likely to be included in the sample. For instance, if a political survey is done by stopping people walking in the Bronx, this will not represent all of New York City. It is often difficult to discern what sub-population a convenience sample represents.

Similarly, a volunteer sample is one in which people's responses are solicited and those who choose to participate, respond. This is a problem because those who choose to participate may tend to have different opinions than the rest of the population, resulting in a biased sample.

Guided Practice 1.4.9

We can easily access ratings for products, sellers, and companies through websites. These ratings are based only on those people who go out of their way to provide a rating. If 50% of online reviews for a product are negative, do you think this means that 50% of buyers are dissatisfied with the product? 5 Answers will vary. From our own anecdotal experiences, we believe people tend to rant more about products that fell below expectations than rave about those that perform as expected. For this reason, we suspect there is a negative bias in product ratings on sites like Amazon. However, since our experiences may not be representative, we also keep an open mind.

The act of taking a random sample helps minimize bias; however, bias can crop up in other ways. Even when people are picked at random, e.g. for surveys, caution must be exercised if the non-response is high. For instance, if only 30% of the people randomly sampled for a survey actually respond, then it is unclear whether the results are representative of the entire population. This non-response bias can skew results.

Even if a sample has no selection bias and no non-response bias, there is an additional type of bias that often crops up and undermines the validity of results, known as response bias. Response bias refers to a broad range of factors that influence how a person responds, such as question wording, question order, and influence of the interviewer. This type of bias can be present even when we collect data from an entire population in what is called a census. Because response bias is often subtle, one must pay careful attention to how questions were asked when attempting to draw conclusions from the data.

Example 1.4.11

Suppose a high school student wants to investigate the student body's opinions on the food in the cafeteria. Let's assume that she manages to survey every student in the school. How might response bias arise in this context?

There are many possible correct answers to this question. For example, students might respond differently depending upon who asks the question, such as a school friend or someone who works in the cafeteria. The wording of the question could introduce response bias. Students would likely respond differently if asked “Do you like the food in the cafeteria?” versus “The food in the cafeteria is pretty bad, don't you think?”

TIP: Watch out for bias

Selection bias, non-response bias, and response bias can still exist within a random sample. Always determine how a sample was chosen, ask what proportion of people failed to respond, and critically examine the wording of the questions.

When there is no bias in a sample, increasing the sample size tends to increase the precision and reliability of the estimate. When a sample is biased, it may be impossible to decipher helpful information from the data, even if the sample is very large.

Guided Practice 1.4.12

A researcher sends out questionnaires to 50 randomly selected households in a particular town asking whether or not they support the addition of a traffic light in their neighborhood. Because only 20% of the questionnaires are returned, she decides to mail questionnaires to 50 more randomly selected households in the same neighborhood. Comment on the usefulness of this approach. 6 The researcher should be concerned about non-response bias, and sampling more people will not eliminate this issue. The same type of people that did not respond to the first survey are likely not going to respond to the second survey. Instead, she should make an effort to reach out to the households from the original sample that did not respond and solicit their feedback, possibly by going door-to-door.

Subsection 1.4.3 Simple, systematic, stratified, cluster, and multistage sampling

Almost all statistical methods for observational data rely on a sample being random and unbiased. When a sample is collected in a biased way, these statistical methods will not generally produce reliable information about the population.

The idea of a simple random sample was introduced in the last section. Here we provide a more technical treatment of this method and introduce four new random sampling methods: systematic, stratified, cluster, and multistage. 7 Systematic and Multistage sampling are not part of the AP syllabus. Figure 1.4.13 provides a graphical representation of simple versus systematic sampling while Figure 1.4.15 provides a graphical representation of stratified, cluster, and multistage sampling.

Simple random sampling is probably the most intuitive form of random sampling. Consider the salaries of Major League Baseball (MLB) players, where each player is a member of one of the league's 30 teams. For the 2010 season, N, the population size or total number of players, is 828. To take a simple random sample of n = 120 of these baseball players and their salaries, we could number each player from 1 to 828. Then we could randomly select 120 numbers between 1 and 828 (without replacement) using a random number generator or random digit table. The players with the selected numbers would comprise our sample.

Two properties are always true in a simple random sample:

Each case in the population has an equal chance of being included in the sample.

Each group of n cases has an equal chance of making up the sample.

The statistical methods in this book focus on data collected using simple random sampling. Note that Property 2 — that each group of n cases has an equal chance making up the sample — is not true for the reidxing four sampling techniques. As you read each one, consider why.

Though less common than simple random sampling, systematic sampling is sometimes used when there exists a convenient list of all of the individuals of the population. Suppose we have a roster with the names of all the MLB players from the 2010 season. To take a systematic random sample, number them from 1 to 828. Select one random number between 1 and 828 and let that player be the first individual in the sample. Then, depending on the desired sample size, select every 10th number or 20th number, for example, to arrive at the sample. 8 If we want a sample of size n = 138, it would make sense to select every 6th player since \(828/138 = 6\text{.}\) Suppose we randomly select the number 810. Then player 810, 816, 822, 828, 6, 12, \(\cdots\) , 798, and 804 would make up the sample. If there are no patterns in the salaries based on the numbering then this could be a reasonable method.

Example 1.4.14

A systematic sample is not the same as a simple random sample. Provide an example of a sample that can come from a simple random sample but not from a systematic random sample.

Answers can vary. If we take a sample of size 3, then it is possible that we could sample players numbered 1, 2, and 3 in a simple random sample. Such a sample would be impossible from a systematic sample. Property 2 of simple random samples does not hold for other types of random samples.

Sometimes there is a variable that is known to be associated with the quantity we want to estimate. In this case, a stratified random sample might be selected. Stratified sampling is a divide-and-conquer sampling strategy. The population is divided into groups called strata. The strata are chosen so that similar cases are grouped together and a sampling method, usually simple random sampling, is employed to select a certain number or a certain proportion of the whole within each stratum. In the baseball salary example, the 30 teams could represent the strata; some teams have a lot more money (we're looking at you, Yankees).

Example 1.4.16

For this baseball example, briefly explain how to select a stratified random sample of size n = 120.

Each team can serve as a stratum, and we could take a simple random sample of 4 players from each of the 30 teams, yielding a sample of 120 players.

Stratified sampling is inherently different than simple random sampling. For example, the stratified sampling approach described would make it impossible for the entire Yankees team to be included in the sample.

Example 1.4.17

Stratified sampling is especially useful when the cases in each stratum are very similar with respect to the outcome of interest. Why is it good for cases within each stratum to be very similar?

We should get a more stable estimate for the subpopulation in a stratum if the cases are very similar. These improved estimates for each subpopulation will help us build a reliable estimate for the full population. For example, in a simple random sample, it is possible that just by random chance we could end up with proportionally too many Yankees players in our sample, thus overestimating the true average salary of all MLB players. A stratified random sample can assure proportional representation from each team.

Next, let's consider a sampling technique that randomly selects groups of people. Cluster sampling is much like simple random sampling, but instead of randomly selecting individuals, we randomly select groups or clusters. Unlike stratified sampling, cluster sampling is most helpful when there is a lot of case-to-case variability within a cluster but the clusters themselves don't look very different from one another. That is, we expect strata to be self-similar (homogeneous), while we expect clusters to be diverse (heterogeneous).

Sometimes cluster sampling can be a more economical random sampling technique than the alternatives. For example, if neighborhoods represented clusters, this sampling method works best when each neighborhood is very diverse. Because each neighborhood itself encompasses diversity, a cluster sample can reduce the time and cost associated with data collection, because the interviewer would need only go to some of the neighborhoods rather than to all parts of a city, in order to collect a useful sample.

Multistage sampling, also called multistage cluster sampling, is a two (or more) step strategy. The first step is to take a cluster sample, as described above. Then, instead of including all of the individuals in these clusters in our sample, a second sampling method, usually simple random sampling, is employed within each of the selected clusters. In the neighborhood example, we could first randomly select some number of neighborhoods and then take a simple random sample from just those selected neighborhoods. As seen in Figure 1.4.15, stratified sampling requires observations to be sampled from every stratum. Multistage sampling selects observations only from those clusters that were randomly selected in the first step.

It is also possible to have more than two steps in multistage sampling. Each cluster may be naturally divided into subclusters. For example, each neighborhood could be divided into streets. To take a three-stage sample, we could first select some number of clusters (neighborhoods), and then, within the selected clusters, select some number of subclusters (streets). Finally, we could select some number of individuals from each of the selected streets.

Example 1.4.18

Suppose we are interested in estimating the proportion of students at a certain school that have part-time jobs. It is believed that older students are more likely to work than younger students. What sampling method should be employed? Describe how to collect such a sample to get a sample size of 60.

Because grade level affects the likelihood of having a part-time job, we should take a stratified random sample. To do this, we can take a simple random sample of 15 students from each grade. This will give us equal representation from each grade. Note: in a simple random sample, just by random chance we might get too many students who are older or younger, which could make the estimate too high or too low. Also, there are no well-defined clusters in this example. We wouldn't want to use the grades as clusters and sample everyone from a couple of the grades. This would create too large a sample and would not give us the nice representation from each grade afforded by the stratified random sample.

Example 1.4.19

Suppose we are interested in estimating the malaria rate in a densely tropical portion of rural Indonesia. We learn that there are 30 villages in that part of the Indonesian jungle, each more or less similar to the next. Our goal is to test 150 individuals for malaria. What sampling method should be employed?

A simple random sample would likely draw individuals from all 30 villages, which could make data collection extremely expensive. Stratified sampling would be a challenge since it is unclear how we would build strata of similar individuals. However, multistage cluster sampling seems like a very good idea. First, we might randomly select half the villages, then randomly select 10 people from each. This would probably reduce our data collection costs substantially in comparison to a simple random sample and would still give us reliable information.

Caution: Advanced sampling techniques require advanced methods

The methods of inference covered in this book generally only apply to simple random samples. More advanced analysis techniques are required for systematic, stratified, cluster, and multistage random sampling.