Section1.2Fractions and Fraction Arithmetic

¶Subsection1.2.1Breaking Apart Fractions

The word “fraction” comes from the Latin word fractio, which means “break into pieces.” Ancient cultures all over the world use fractions to understand parts of wholes, but it took humanity thousands of years to develop the symbols we use today.

Subsubsection1.2.1.1Parts of a Whole

One approach to understanding fractions is to think of them as counting parts of a whole.

one whole

three sevenths

In Figure 1.2.1, we see \(1\) whole amount divided into \(7\) parts. Since \(3\) of the \(7\) parts are highlighted, we have an illustration of the fraction \(\frac{3}{7}\text{.}\) The denominator \(7\) lets us know how many equal parts of the whole amount we're considering; since we've got \(7\) parts here, they're called “sevenths.” The numerator \(3\) tells us how many of those sevenths we're considering.

Checkpoint1.2.2A Fraction as Parts of a Whole

Instead of using rectangles, we can also locate fractions on number lines. When a number line is marked off with whole numbers, equal divisions of the unit \(1\) can represent the equal parts, as in Figure 1.2.3.

Checkpoint1.2.4A Fraction on a Number Line

Subsubsection1.2.1.2Division

Another helpful way to understand fractions like \(\frac{3}{7}\) is to see them as division of the numerator by the denominator. In this case, \(3\) is divided into \(7\) parts, as in Figure 1.2.5.

Checkpoint1.2.6Seeing a Fraction as Division Arithmetic

Subsection1.2.2Equivalent Fractions

It's common to have two fractions that represent the same amount. Consider \(\frac{2}{5}\) and \(\frac{6}{15}\) represented in various ways in Figures 1.2.7–1.2.9.

Those two fractions, \(\frac{2}{5}\) and \(\frac{6}{15}\) are equal, as those figures demonstrate. Also, because they each equal \(0.4\) as a decimal. If we must work with this number, the fraction that uses smaller numbers, \(\frac{2}{5}\text{,}\) is preferable. Working with smaller numbers decreases the likelihood of making a human arithmetic error. And it also increases the chances that you might make useful observations about the nature of that number.

So if you are handed a fraction like \(\frac{6}{15}\text{,}\) it is important to try to reduce it to “lowest terms.” The most important skill you can have to help you do this is to know the multiplication table very well. If you know it well, you know that \(6=2\cdot3\) and \(15=3\cdot5\text{,}\) so you know

Both the numerator and denominator were divisible by \(3\text{,}\) so they could be “factored out” and then as factors, canceled out.

Checkpoint1.2.10

Sometimes it is useful to do the opposite of reducing a fraction, and build up the fraction to use larger numbers.

Checkpoint1.2.11

Subsection1.2.3Multiplying with Fractions

To double a recipe or cut it in half, we need to consider fractions of fractions.

Example1.2.12

Say a recipe calls for \(\frac{2}{3}\) cup of milk, but we’d like to double the recipe. One way to measure this out is to fill a measuring cup to \(\frac{2}{3}\text{,}\) two times:

Altogether there are four thirds of a whole here. So \(\frac{2}{3} \cdot 2 = \frac{4}{3}\text{.}\) The figure shows \(\frac{2}{3}\) of two wholes. Two wholes can be written as \(2\text{,}\) or as the fraction \(\frac{2}{1}\text{.}\) So mathematically, our figure says

Example1.2.13

We could also use multiplication to decrease amounts. How much is \(\frac{1}{2}\) of \(\frac{2}{3}\) cup?

So \(\frac{1}{2}\) of \(\frac{2}{3}\) cup is \(\frac{2}{6}\) cup. Mathematically, we can write

In our two examples, we have observed that

This idea works generally, no matter what numbers are involved with the fractions.

Fact1.2.14Multiplication with Fractions

As long as \(b\) and \(d\) are not \(0\text{,}\) then fractions multiply this way:

Try some fraction multiplications for practice:

Checkpoint1.2.15

Subsection1.2.4Division with Fractions

How does division with fractions work? Are we able to compute/simplify each of these examples?

We know that when we divide something by \(2\text{,}\) this is the same as multiplying it by \(\frac{1}{2}\text{.}\) Conversely, dividing a number or expression by \(\frac{1}{2}\) is the same as multiplying by \(\frac{2}{1}\text{,}\) or just \(2\text{.}\) The more general property is that when we divide a number or expression by \(\frac{a}{b}\text{,}\) this is equivalent to multiplying by the reciprocal \(\frac{b}{a}\text{.}\)

Fact1.2.16Division with Fractions

As long as \(b\text{,}\) \(c\) and \(d\) are not \(0\text{,}\) then division with fractions works this way:

Example1.2.17

With our examples from the beginning of this subsection:

Try some divisions with fractions for practice:

Checkpoint1.2.18

Subsection1.2.5Adding and Subtracting Fractions

With whole numbers and integers, operations of addition and subtraction are relatively straightforward. The situation is almost as straightforward with fractions if the two fractions have the same denominator. Consider

In the same way that \(7\) tacos and \(3\) tacos make \(10\) tacos, we have:

Fact1.2.19Adding/Subtracting with Fractions Having the Same Denominator

To add or subtract two fractions having the same denominator, keep that denominator, and add or subtract the numerators.

If it's possible, useful, or required of you, simplify the result by reducing to lowest terms.

Checkpoint1.2.20

Whenever we'd like to combine fractional amounts that don't represent the same number of parts of a whole (that is, when the denominators are different), finding sums and differences is more complicated.

Example1.2.21Quarters and Dimes

Find the sum \(\frac{3}{4}+\frac{2}{10}\text{.}\) Does this seem intimidating? Consider this:

\(\frac{1}{4}\) of a dollar is a quarter, and so \(\frac{3}{4}\) of a dollar is \(75\) cents.

\(\frac{1}{10}\) of a dollar is a dime, and so \(\frac{2}{10}\) of a dollar is \(20\) cents.

So if you know what to look for, the expression \(\frac{3}{4}+\frac{2}{10}\) is like adding \(75\) cents and \(20\) cents, which gives you \(95\) cents. As a fraction of one dollar, that is \(\frac{95}{100}\text{.}\) So we can report

(Although we should probably reduce that last fraction to \(\frac{19}{20}\text{.}\))

This example was not something you can apply to other fraction addition situations, because the denominators here worked especially well with money amounts. But there is something we can learn here. The fraction \(\frac{3}{4}\) was equivalent to \(\frac{75}{100}\text{,}\) and the other fraction \(\frac{2}{10}\) was equivalent to \(\frac{20}{100}\text{.}\) These equivalent fractions have the same denominator and are therefore “easy” to add. What we saw happen was:

This realization gives us a strategy for adding (or subtracting) fractions.

Fact1.2.22Adding/Subtracting Fractions with Different Denominators

To add (or subtract) generic fractions together, use their denominators to find a common denominator. This means some whole number that is a whole multiple of both of the original denominators. Then rewrite the two fractions as equivalent fractions that use this common denominator. Write the result keeping that denominator and adding (or subtracting) the numerators. Reduce the fraction if that is useful or required.

Example1.2.23

Let's add \(\frac{2}{3}+\frac{2}{5}\text{.}\) The denominators are \(3\) and \(5\text{,}\) so the number \(15\) would be a good common denominator.

Checkpoint1.2.24

Subsection1.2.6Mixed Numbers and Improper Fractions

A simple recipe for bread contains only a few ingredients:

| \(1\,\sfrac{1}{2}\) | tablespoons yeast |

| \(1\,\sfrac{1}{2}\) | tablespoons kosher salt |

| \(6\,\sfrac{1}{2}\) | cups unbleached, all-purpose flour (more for dusting) |

Each ingredient is listed as a mixed number that quickly communicates how many whole amounts and how many parts are needed. It's useful for quickly communicating a practical amount of something you are cooking with, measuring on a ruler, purchasing at the grocery store, etc. But it causes trouble in an algebra class. The number \(1\,\sfrac{1}{2}\) means “one and one half.” So really,

The trouble is that with \(1\,\sfrac{1}{2}\text{,}\) you have two numbers written right next to each other. Normally with two math expressions written right next to each other, they should be multiplied, not added. But with a mixed number, they should be added.

Fortunately we just reviewed how to add fractions. If we need to do any arithmetic with a mixed number like \(1\,\sfrac{1}{2}\text{,}\) we can treat it as \(1+\frac{1}{2}\) and simplify to get a “nice” fraction instead:

A fraction like \(\frac{3}{2}\) is called an improper fraction because it's actually larger than \(1\text{.}\) And a “proper” fraction would be something small that is only part of a whole instead of more than a whole.

SubsectionExercises

Multiplying/Dividing Fractions

1

Multiply these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{ \frac{4}{9} \cdot \frac{5}{9} }\)

2

Multiply these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{ \frac{2}{7} \cdot \frac{2}{9} }\)

3

Multiply these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{ \frac{15}{7} \cdot \frac{5}{3} }\)

4

Multiply these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{ \frac{3}{2} \cdot \frac{5}{12} }\)

5

Multiply these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{8}{3} \cdot \frac{7}{22}}\)

6

Multiply these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{14}{13} \cdot \frac{7}{6}}\)

7

Multiply the integer with the fraction: \(\displaystyle{15\cdot\left( -{\frac{4}{3}} \right)}\)

8

Multiply the integer with the fraction: \(\displaystyle{45\cdot\left( -{\frac{5}{9}} \right)}\)

9

Multiply these fractions: \(\displaystyle{ {{\frac{7}{25}}} \cdot {{\frac{6}{49}}} \cdot {{\frac{5}{4}}} }\)

10

Multiply these fractions: \(\displaystyle{ {{\frac{6}{25}}} \cdot {{\frac{7}{9}}} \cdot {{\frac{5}{49}}} }\)

11

Carry out the division: \(\displaystyle{ \frac{5}{6} \div \frac{8}{5} }\)

12

Carry out the division: \(\displaystyle{ \frac{5}{8} \div \frac{8}{5} }\)

13

Carry out the division: \(\displaystyle{ \frac{2}{15} \div \left(-\frac{5}{9}\right) }\)

14

Carry out the division: \(\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{6} \div \left(-\frac{8}{9}\right) }\)

15

Carry out the division: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{10}{9} \div (-25) }\)

16

Carry out the division: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{12}{7} \div (-8) }\)

17

Carry out the division: \(\displaystyle{12 \div \frac{3}{4} }\)

18

Carry out the division: \(\displaystyle{9 \div \frac{9}{4} }\)

19

Multiply the following: \(\displaystyle{{1 {\textstyle\frac{11}{25}}} \cdot {1 {\textstyle\frac{7}{18}}} }\)

20

Multiply the following: \(\displaystyle{{1 {\textstyle\frac{3}{25}}} \cdot {2 {\textstyle\frac{11}{12}}} }\)

Adding/Subtracting Fractions

21

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{\frac{1}{20} + \frac{1}{20}}\)

22

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{\frac{1}{24} + \frac{19}{24}}\)

23

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{\frac{3}{10} + \frac{31}{60}}\)

24

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{\frac{1}{9} + \frac{4}{27}}\)

25

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{\frac{4}{9} + \frac{19}{45}}\)

26

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{\frac{5}{6} + \frac{7}{30}}\)

27

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{\frac{3}{8} + \frac{4}{9}}\)

28

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{\frac{2}{9} + \frac{1}{6}}\)

29

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{\frac{1}{5} + \frac{3}{10}}\)

30

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{\frac{1}{6} + \frac{3}{10}}\)

31

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{1}{5} + \frac{3}{5}}\)

32

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{2}{5} + \frac{4}{5}}\)

33

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{2}{9} + \frac{16}{27}}\)

34

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{1}{10} + \frac{7}{60}}\)

35

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{7}{8} + \frac{2}{5}}\)

36

Add these two fractions: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{5}{8} + \frac{3}{5}}\)

37

Add these together: \(\displaystyle{ 3 + \frac{3}{4}}\)

38

Add these together: \(\displaystyle{ 4 + \frac{1}{10}}\)

39

Add these fractions: \(\displaystyle{ {{\frac{2}{5}}} + {{\frac{1}{10}}} + {{\frac{1}{3}}} }\)

40

Add these fractions: \(\displaystyle{ {{\frac{1}{3}}} + {{\frac{1}{5}}} + {{\frac{1}{6}}} }\)

41

Subtract one fraction from the other: \(\displaystyle{\frac{11}{12} - \frac{1}{12}}\)

42

Subtract one fraction from the other: \(\displaystyle{\frac{15}{14} - \frac{9}{14}}\)

43

Subtract one fraction from the other: \(\displaystyle{\frac{29}{50} - \frac{3}{10}}\)

44

Subtract one fraction from the other: \(\displaystyle{\frac{23}{60} - \frac{3}{10}}\)

45

Subtract one fraction from the other: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{3}{10}-\frac{1}{6}}\)

46

Subtract one fraction from the other: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{3}{10}-\frac{1}{6}}\)

47

Subtract one fraction from the other: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{3}{10} - \left(-\frac{4}{5}\right)}\)

48

Subtract one fraction from the other: \(\displaystyle{-\frac{5}{6} - \left(-\frac{3}{10}\right)}\)

49

Carry out the subtraction: \(\displaystyle{ -5 - \frac{11}{2}}\)

50

Carry out the subtraction: \(\displaystyle{ -4 - \frac{13}{8}}\)

Use your fraction arithmetic skills to solve some applications.

51

Jon walked \({{\frac{1}{6}}}\) of a mile in the morning, and then walked \({{\frac{4}{11}}}\) of a mile in the afternoon. How far did Jon walk altogether?

Jon walked a total of of a mile.

52

Kimball and Kenji are sharing a pizza. Kimball ate \({{\frac{1}{7}}}\) of the pizza, and Kenji ate \({{\frac{1}{6}}}\) of the pizza. How much of the pizza was eaten in total?

They ate of the pizza.

53

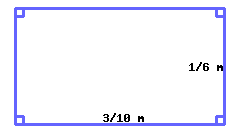

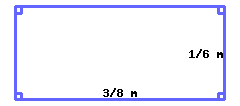

Find the perimeter of the rectangle.

Its perimeter is meters. (Use a fraction in your answer.)

54

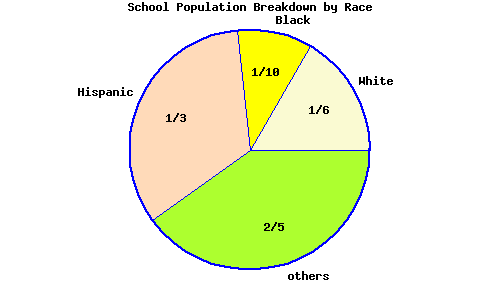

The pie chart represents a school’s student population.

Fill in the blank with a fraction.

Together, white and black students make up of the school’s population.

55

A trail’s total length is \({{\frac{25}{63}}}\) of a mile. It has two legs. The first leg is \({{\frac{2}{7}}}\) of a mile long. How long is the second leg?

The second leg is of a mile in length.

56

Each page of a book is \({5 {\textstyle\frac{5}{6}}}\) inches in height, and consists of a header (a top margin), a footer (a bottom margin), and the middle part (the body). The header is \({{\frac{7}{9}}}\) of an inch thick and the middle part is \({4 {\textstyle\frac{1}{9}}}\) inches from top to bottom.

What is the thickness of the footer?

The footer is of an inch thick.

57

Hayden and Eric are sharing a pizza. Hayden ate \({{\frac{3}{10}}}\) of the pizza, and Eric ate \({{\frac{1}{8}}}\) of the pizza. How much more pizza did Hayden eat than Eric?

Hayden ate more of the pizza than Eric ate.

58

A school had a fund raising event. The revenue came from three resources: ticket sales, auction sales, and donations. Ticket sales account for \({{\frac{3}{5}}}\) of the total revenue; auction sales account for \({{\frac{3}{8}}}\) of the total revenue. What fraction of the revenue came from donations?

of the revenue came from donations.

59

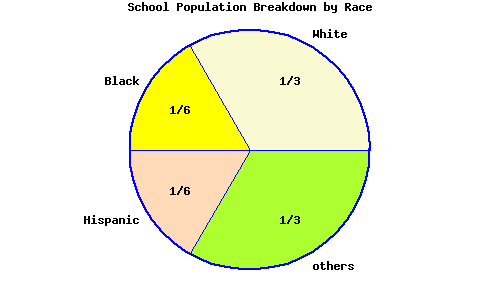

The pie chart represents a school’s student population.

Answer the following question with fraction.

more of the school is white students than black students.

60

A few years back, a car was purchased for \({\$14{,}000}\text{.}\) Today it is worth \({{\frac{1}{4}}}\) of its original value. What is the car’s current value?

The car’s current value is .

61

A town has \(200\) residents in total, of which \({{\frac{3}{4}}}\) are Native Americans. How many Native Americans reside in this town?

There are Native Americans residing in this town.

62

A company received a grant, and decided to spend \({{\frac{5}{6}}}\) of this grant in research and development next year. Out of the money set aside for research and development, \({{\frac{2}{3}}}\) will be used to buy new equipment. What fraction of the grant will be used to buy new equipment?

of the grant will be used to buy new equipment.

63

Find the area of the rectangle.

Its area is square meters. (Use a fraction in your answer.)

64

A food bank just received \(16\) kilograms of emergency food. Each family in need is to receive \({{\frac{2}{5}}}\) kilograms of food. How many families can be served with the \(16\) kilograms of food?

families can be served with the \(16\) kilograms of food.

65

A construction team maintains a \({75}\)-mile-long sewage pipe. Each day, the team can cover \({{\frac{5}{9}}}\) of a mile. How many days will it take the team to complete the maintenance of the entire sewage pipe?

It will take the team days to complete maintaining the entire sewage pipe.

66

A child is stacking up tiles. Each tile’s height is \({{\frac{2}{3}}}\) of a centimeter. How many layers of tiles are needed to reach \({12}\) centimeters in total height?

To reach the total height of \({12}\) centimeters, layers of tiles are needed.

67

A restaurant made \(100\) cups of pudding for a festival.

Customers at the festival will be served \({{\frac{1}{9}}}\) of a cup of pudding per serving. How many customers can the restaurant serve at the festival with the \(100\) cups of pudding?

The restaurant can serve customers at the festival with the \(100\) cups of pudding.

68

A \(2\times4\) piece of lumber in your garage is \({66 {\textstyle\frac{1}{4}}}\) inches long. A second \(2\times4\) is \({38 {\textstyle\frac{1}{8}}}\) inches long. If you lay them end to end, what will the total length be?

The total length will be inches.

69

A \(2\times4\) piece of lumber in your garage is \({42 {\textstyle\frac{1}{8}}}\) inches long. A second \(2\times4\) is \({68 {\textstyle\frac{1}{4}}}\) inches long. If you lay them end to end, what will the total length be?

The total length will be inches.

70

Each page of a book consists of a header, a footer and the middle part. The header is \({{\frac{7}{10}}}\) inches in height; the footer is \({{\frac{9}{20}}}\) inches in height; and the middle part is \({6 {\textstyle\frac{1}{10}}}\) inches in height.

What is the total height of each page in this book? Use mixed number in your answer if needed.

Each page in this book is inches in height.

71

When driving on a high way, noticed a sign saying exit to Johnstown is \(1{{\frac{1}{2}}}\) miles away, while exit to Jerrystown is \(3{{\frac{1}{4}}}\) miles away. How far is Johnstown from Jerrystown?

Johnstown and Jerrystown are miles apart.

72

A cake recipe needs \({1 {\textstyle\frac{1}{5}}}\) cups of flour. Using this recipe, to bake \(6\) cakes, how many cups of flour are needed?

To bake \(6\) cakes, cups of flour are needed.

73

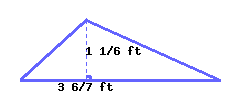

Find the area of the triangle.

Its area is square feet. (Use a fraction in your answer.)

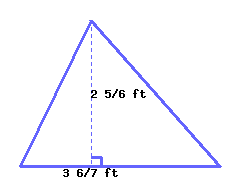

74

Find the area of the triangle.

Its area is square feet. (Use a fraction in your answer.)