Section 11.5 Technical Definition of a Function

¶Objectives: PCC Course Content and Outcome Guide

In Section 11.1, we discussed a conceptual understanding of functions and Definition 11.1.3. In this section we'll start with a more technical definition of what is a function, consistent with the ideas from Section 11.1.

Subsection 11.5.1 Formally Defining a Function

¶Definition 11.5.2. Function (Technical Definition).

A function is a collection of ordered pairs \((x,y)\) such that any particular value of \(x\) is paired with at most one value for \(y\text{.}\)

How is this definition consistent with the informal Definition 11.1.3, which describes a function as a process? Well, if you have a collection of ordered pairs \((x,y)\text{,}\) you can choose to view the left number as an input, and the right value as the output. If the function's name is \(f\) and you want to find \(f(x)\) for a particular number \(x\text{,}\) look in the collection of ordered pairs to see if \(x\) appears among the first coordinates. If it does, then \(f(x)\) is the (unique) \(y\)-value it was paired with. If it does not, then that \(x\) is just not in the domain of \(f\text{,}\) because you have no way to determine what \(f(x)\) would be.

Example 11.5.3.

Using Definition 11.5.1, a function \(f\) could be given by \(\{(1,4), (2,3), (5,3), (6,1)\}\text{.}\)

What is \(f(1)?\) Since the ordered pair \((1,4)\) appears in the collection of ordered pairs, \(f(1)=4\text{.}\)

What is \(f(2)?\) Since the ordered pair \((2,3)\) appears in the collection of ordered pairs, \(f(2)=3\text{.}\)

What is \(f(3)?\) None of the ordered pairs in the collection start with \(3\text{,}\) so \(f(3)\) is undefined, and we would say that \(3\) is not in the domain of \(f\text{.}\)

Example 11.5.4. A Function Given as a Table.

Consider the function \(g\) expressed by Figure 11.5.5. How is this “a collection of ordered pairs?” With tables the connection is most easily apparent. Pair off each \(x\)-value with its \(y\)-value.

| \(x\) | \(g(x)\) |

| 12 | \(0.16\) |

| 15 | \(3.2\) |

| 18 | \(1.4\) |

| 21 | \(1.4\) |

| 24 | \(0.98\) |

In this case, we can view this function as:

Example 11.5.6. A Function Given as a Formula.

Consider the function \(h\) expressed by the formula \(h(x)=x^2\text{.}\) How is this “a collection of ordered pairs?”

This time, the collection is really big. Imagine an \(x\)-value, like \(x=2\text{.}\) We can calculate that \(f(2)=2^2=4\text{.}\) So the input \(2\) pairs with the output \(4\) and the ordered pair \((2,4)\) is part of the collection.

You could move on to any \(x\)-value, like say \(x=2.1\text{.}\) We can calculate that \(f(2.1)=2.1^2=4.41\text{.}\) So the input \(2.1\) pairs with the output \(4.41\) and the ordered pair \((2.1,4.41)\) is part of the collection.

The collection is so large that we cannot literally list all the ordered pairs as was done in Example 11.5.3 and Example 11.5.4. We just have to imagine this giant collection of ordered pairs. And if it helps to conceptualize it, we know that the ordered pairs \((2,4)\) and \((2.1,4.41)\) are included.

Example 11.5.7. A Function Given as a Graph.

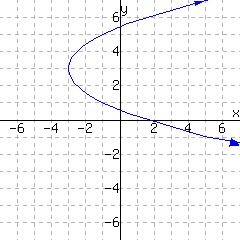

Consider the functions \(p\) and \(q\) expressed in Figure 11.5.8 and Figure 11.5.9. How is each of these “a collection of ordered pairs?”

In Figure 11.5.8, we see that \(p(1)=4\text{,}\) \(p(2)=3\text{,}\) \(p(5)=3\text{,}\) and \(p(6)=1\text{.}\) The graph literally is the collection

In Figure 11.5.9, we can see a few whole number function values, like \(q(0)=0\) and \(q(1)=2\text{.}\) But the entire curve has infinitely many points on it and we'd never be able to list them all. We just have to imagine the giant collection of ordered pairs. And if it helps to conceptualize it, we know that the ordered pairs \((0,0)\) and \((1,2)\) are included.

Checkpoint 11.5.10.

Subsection 11.5.2 Identifying What is Not a Function

Just because you have a set of order pairs, a table, a graph, or an equation, it does not necessarily mean that you have a function. Conceptually, whatever you have needs to give consistent outputs if you feed it the same input. More technically, the set of ordered pairs is not allowed to have two ordered pairs that have the same \(x\)-value but different \(y\)-values.

Example 11.5.11.

Consider each set of ordered pairs. Does it make a function?

\(\left\{\left(5,9\right),\left(3,2\right),\left(\frac{1}{2},0.6\right),\left(5,1\right)\right\}\)

\(\left\{\left(-5,12\right),\left(3,7\right),\left(\sqrt{2},1\right),\left(-0.9,4\right)\right\}\)

\(\left\{\left(5,9\right),\left(3,9\right),\left(4.2,\sqrt{2}\right),\left(\frac{4}{3},\frac{1}{2}\right)\right\}\)

\(\left\{\left(5,9\right),\left(0.7,2\right),\left(\sqrt{25},3\right),\left(\frac{2}{3},\frac{3}{2}\right)\right\}\)

This set of ordered pairs is not a function. The problem is that it has both \((5,9)\) and \((5,1)\text{.}\) It uses the same \(x\)-value paired with two different \(y\)-values. We have no clear way to turn the input \(5\) into an output.

This set of ordered pairs is a function. It is a collection of ordered pairs, and the \(x\)-values are never reused.

This set of ordered pairs is a function. It is a collection of ordered pairs, and the \(x\)-values are never reused. You might note that the output value \(9\) appears twice, but that doesn't matter. That just tells us that the function turns \(5\) into \(9\) and it also turns \(3\) into \(9\text{.}\)

This set of ordered pairs is not a function, but it's a little tricky. One of the ordered pairs uses \(\sqrt{25}\) as an input value. But that is the same as \(5\text{,}\) which is also used as an input value.

Now that we understand how some sets of ordered pairs might not be functions, what about tables, graphs, and equations? If we are handed one of these things, can we tell whether or not it is giving us a function?

Checkpoint 11.5.12. Does This Table Make a Function?

Example 11.5.13. Does This Graph Make a Function?

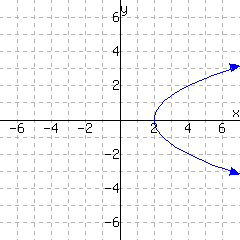

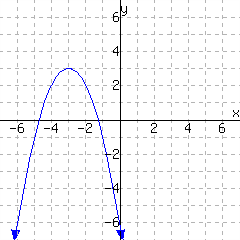

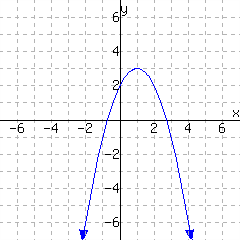

Which of these graphs make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{?}\)

The graph in Figure 11.5.14 does not make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) Two ordered pairs on that graph are \((-3,1)\) and \((-3,-2)\text{,}\) so an input value is used twice with different output values.

The graph in Figure 11.5.15 does not make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) There are many ordered pairs with the same input value but different output values. For example, \((2,-2)\) and \((2,4)\text{.}\)

The graph in Figure 11.5.16 does make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) It appears that no matter what \(x\)-value you choose on the \(x\)-axis, there is exactly one \(y\)-value paired up with it on the graph.

The graph in Figure 11.5.17 does make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{,}\) but we should discuss. The hollow dots on the line indicate that the line goes right up to that point, but never reaches it. We say there is a “hole” in the graph at these places. For two of these holes, there is a separate ordered pair immediately above or below the hole. The graph has the ordered pair \((-4,4)\text{.}\) It also has ordered pairs like \((\text{very close to }{-4},\text{very close to }0)\text{,}\) but it does not have \((-4,0)\text{.}\) Overall, there is no \(x\)-value that is used twice with different \(y\)-values, so this graph does make \(y\) a function of \(x\)

The graph in Figure 11.5.15 does not make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) There are many ordered pairs with the same input value but different output values. For example, \((0,1)\text{,}\) \((0,3)\text{,}\) \((0,-1)\text{,}\) \((0,5)\text{,}\) and \((0,-6)\) all use \(x=0\text{.}\)

The graph in Figure 11.5.15 does not make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) There are many ordered pairs with the same input value but different output values. For example at \(x=2\text{,}\) there is both a positive and a negative associated \(y\)-value. It's hard to say exactly what these \(y\)-values are, but we don't have to.

This last set of examples might reveal something to you. For instance in Figure 11.5.15, the issue is that there are places on the graph with the same \(x\)-value, but different \(y\)-values. Visually, what that means is there are places on the graph that are directly above/below each other. Thinking about this leads to a quick visual “test” to determine if a graph gives \(y\) as a function of \(x\text{.}\)

Fact 11.5.20. Vertical Line Test.

Given a graph in the \(xy\)-plane, if a vertical line ever touches it in more than one place, the graph does not give \(y\) as a function of \(x\text{.}\) If vertical lines only ever touch the graph once or never at all, then the graph does give \(y\) as a function of \(x\text{.}\)

Example 11.5.21.

In each graph from Example 11.5.13, we can apply the Vertical Line Test.

Lastly, we come to equations. Certain equations with variables \(x\) and \(y\) clearly make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) For example, \(y=x^2+1\) says that if you have an \(x\)-value, all you have to do is substitute it into that equation and you will have determined an output \(y\)-value. You could then name the function \(f\) and give a formula for it: \(f(x)=x^2+1\text{.}\)

With other equations, it may not be immediately clear whether or not they make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\)

Example 11.5.28.

Do each of these equations make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{?}\)

\(2x+3y=5\)

\(y=\pm\sqrt{x+4}\)

\(x^2+y^2=9\)

-

The equation \(2x+3y=5\) does make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) Here are three possible explanations.

You recognize that the graph of this equation would be a non-vertical line, and so it would pass the Vertical Line Test.

Imagine that you have a specific value for \(x\) and you substitute it in to \(2x+3y=5\text{.}\) Will you be able to use algebra to solve for \(y\text{?}\) All you will need is to simplify, subtract from both sides, and divide on both sides, so you will be able to determine \(y\text{.}\)

Can you just isolate \(y\) in terms of \(x\text{?}\) Yes, a few steps of algebra can turn \(2x+3y=5\) into \(y=\frac{5-2x}{3}\text{.}\) Now you have an explicit formula for \(y\) in terms of \(x\text{,}\) so \(y\) is a function of \(x\text{.}\)

The equation \(y=\pm\sqrt{x+4}\) does not make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) Just having the \(\pm\) (plus or minus) in the equation immediately tells you that for almost any valid \(x\)-value, there would be two associated \(y\)-values.

-

The equation \(x^2+y^2=9\) does not make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) Here are three possible explanations.

Imagine that you have a specific value for \(x\) and you substitute it in to \(x^2+y^2=9\text{.}\) Will you be able to use algebra to solve for \(y\text{?}\) For example, if you substitute in \(x=1\text{,}\) then you have \(1+y^2=9\text{,}\) which simplifies to \(y^2=8\text{.}\) Can you really determine what \(y\) is? No, because it could be \(\sqrt{8}\) or it could be \(-\sqrt{8}\text{.}\) So this equation does not provide you with a way to turn \(x\)-values into \(y\)-values.

Can you just isolate \(y\) in terms of \(x\text{?}\) You might get started and use algebra to convert \(x^2+y^2=9\) into \(y^2=9-x^2\text{.}\) But what now? The best you can do is acknowledge that \(y\) is either the positive or the negative square root of \(9 - x^2\text{.}\) You might write \(y=\pm\sqrt{9-x^2}\text{.}\) But now for almost any valid \(x\)-value, there are two associated \(y\)-values.

You recognize that the graph of this equation would be a circle with radius \(3\text{,}\) and so it would not pass the Vertical Line Test.

Checkpoint 11.5.29.

Reading Questions 11.5.3 Reading Questions

1.

Suppose you have a “relation”. That is, a set of order pairs, a table of \(x\)- and \(y\)-values, a graph, or an equation in \(x\) and \(y\text{.}\) What is the one thing that could happen that would make the relation not be a function?

2.

Explain how to use the vertical line test.

Exercises 11.5.4 Exercises

Determining If Sets of Ordered Pairs Are Functions

1.

Do these sets of ordered pairs make functions of \(x\text{?}\) What are their domains and ranges?

-

\(\Big\{(-10,10),(2,0)\Big\}\)

This set of ordered pairs

describes

does not describe

-

\(\Big\{(-9,3),(-6,2),(-4,6)\Big\}\)

This set of ordered pairs

describes

does not describe

-

\(\Big\{(3,9),(10,0),(3,0),(3,4)\Big\}\)

This set of ordered pairs

describes

does not describe

-

\(\Big\{(-8,6),(-10,10),(-8,7),(3,10),(8,3)\Big\}\)

This set of ordered pairs

describes

does not describe

2.

Do these sets of ordered pairs make functions of \(x\text{?}\) What are their domains and ranges?

-

\(\Big\{(0,7),(3,4)\Big\}\)

This set of ordered pairs

describes

does not describe

-

\(\Big\{(-3,3),(3,3),(6,0)\Big\}\)

This set of ordered pairs

describes

does not describe

-

\(\Big\{(9,9),(6,2),(8,6),(9,10)\Big\}\)

This set of ordered pairs

describes

does not describe

-

\(\Big\{(-8,0),(0,5),(1,7),(4,9),(0,8)\Big\}\)

This set of ordered pairs

describes

does not describe

3.

Does the following set of ordered pairs make for a function of \(x\text{?}\)

\(\Big\{(-1,2),(-1,5),(-7,6),(-6,2),(8,9)\Big\}\)

This set of ordered pairs

describes

does not describe

4.

Does the following set of ordered pairs make for a function of \(x\text{?}\)

\(\Big\{(-10,9),(6,4),(-8,5),(1,2),(-9,9)\Big\}\)

This set of ordered pairs

describes

does not describe

Domain and Range

5.

Below is all of the information that exists about a function \(H\text{.}\)

\(\begin{aligned} H(1)\amp =3\amp H(3)\amp =1\amp H(6)\amp =4 \end{aligned}\)

Write \(H\) as a set of ordered pairs.

\(H\) has domain and range .

6.

Below is all of the information about a function \(K\text{.}\)

\(\begin{aligned} K(a)\amp =2\amp K(b)\amp =1\\ K(c)\amp =-2\amp K(d)\amp =2 \end{aligned}\)

Write \(K\) as a set of ordered pairs.

\(K\) has domain and range .

Determining If Graphs Are Functions

7.

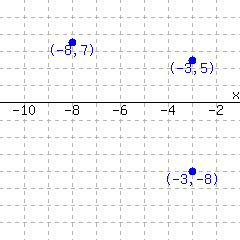

Decide whether each graph shows a relationship where \(y\) is a function of \(x\text{.}\)

The first graph

does

does not

does

does not

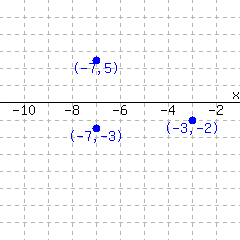

8.

Decide whether each graph shows a relationship where \(y\) is a function of \(x\text{.}\)

The first graph

does

does not

does

does not

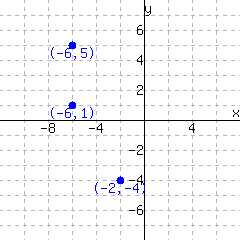

9.

The following graphs show two relationships. Decide whether each graph shows a relationship where \(y\) is a function of \(x\text{.}\)

The first graph

does

does not

does

does not

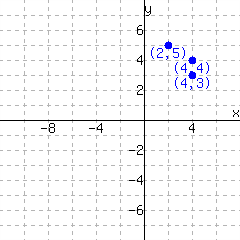

10.

The following graphs show two relationships. Decide whether each graph shows a relationship where \(y\) is a function of \(x\text{.}\)

The first graph

does

does not

does

does not

Determining If Tables Are Functions

11.

Determine whether or not the following table could be the table of values of a function. If the table can not be the table of values of a function, give an input that has more than one possible output.

| Input | Output |

| \(2\) | \(-1\) |

| \(4\) | \(1\) |

| \(6\) | \(-4\) |

| \(8\) | \(18\) |

| \(-2\) | \(-10\) |

Could this be the table of values for a function?

yes

no

If not, which input has more than one possible output?

-2

2

4

6

8

None, the table represents a function.

12.

Determine whether or not the following table could be the table of values of a function. If the table can not be the table of values of a function, give an input that has more than one possible output.

| Input | Output |

| \(2\) | \(4\) |

| \(4\) | \(-13\) |

| \(6\) | \(13\) |

| \(8\) | \(6\) |

| \(-2\) | \(-11\) |

Could this be the table of values for a function?

yes

no

If not, which input has more than one possible output?

-2

2

4

6

8

None, the table represents a function.

13.

Determine whether or not the following table could be the table of values of a function. If the table can not be the table of values of a function, give an input that has more than one possible output.

| Input | Output |

| \(-4\) | \(13\) |

| \(-3\) | \(2\) |

| \(-2\) | \(11\) |

| \(-3\) | \(13\) |

| \(-1\) | \(-18\) |

Could this be the table of values for a function?

yes

no

If not, which input has more than one possible output?

-4

-3

-2

-1

None, the table represents a function.

14.

Determine whether or not the following table could be the table of values of a function. If the table can not be the table of values of a function, give an input that has more than one possible output.

| Input | Output |

| \(-4\) | \(-8\) |

| \(-3\) | \(4\) |

| \(-2\) | \(-14\) |

| \(-3\) | \(19\) |

| \(-1\) | \(0\) |

Could this be the table of values for a function?

yes

no

If not, which input has more than one possible output?

-4

-3

-2

-1

None, the table represents a function.

Determining If Equations Are Functions

15.

Select all of the following relations that make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) There are several correct answers.

\(y=\pm\sqrt{81-x^2}\)

\(y=x^{2}\)

\(x=y^{3}\)

\(y=\sqrt[3]{x}\)

\(y=\frac{1}{x^{2}}\)

\(y=\left| x \right|\)

\(x^2+y^2=81\)

\(5 x+ 4 y=1\)

\(y=\frac{x+7}{8-x}\)

\(\left| y\right|=x\)

\(y=\sqrt{81-x^2}\)

\(x=y^{2}\)

16.

Select all of the following relations that make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) There are several correct answers.

\(x=y^{2}\)

\(5 x+ 5 y=1\)

\(x^2+y^2=16\)

\(y=\frac{1}{x^{3}}\)

\(\left| y\right|=x\)

\(x=y^{3}\)

\(y=\sqrt{36-x^2}\)

\(y=x^{5}\)

\(y=\pm\sqrt{36-x^2}\)

\(y=\left| x \right|\)

\(y=\frac{x+2}{4-x}\)

\(y=\sqrt[8]{x}\)

17.

Some equations involving \(x\) and \(y\) define \(y\) as a function of \(x\text{,}\) and others do not. For example, if \(x+y=1\text{,}\) we can solve for \(y\) and obtain \(y = 1-x\text{.}\) And we can then think of \(y = f(x) = 1-x\text{.}\) On the other hand, if we have the equation \(x=y^2\) then \(y\) is not a function of \(x\text{,}\) since for a given positive value of \(x\text{,}\) the value of \(y\) could equal \(\sqrt{x}\) or it could equal \(-\sqrt{x}\text{.}\) Select all of the following relations that make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) There are several correct answers.

\(\left|y\right| - x = 0\)

\(y + x^2 = 1\)

\(y^2 + x^2 = 1\)

\(3 x + 5 y + 9 = 0\)

\(y - \left|x\right| = 0\)

\(x+y=1\)

\(y^6 + x = 1\)

\(y^3 + x^4 = 1\)

On the other hand, some equations involving \(x\) and \(y\) define \(x\) as a function of \(y\) (the other way round).

Select all of the following relations that make \(x\) a function of \(y\text{.}\) There are several correct answers.

\(y^2 + x^2 = 1\)

\(3 x + 5 y + 9 = 0\)

\(\left|y\right| - x = 0\)

\(y - \left|x\right| = 0\)

\(y^4 + x^5 = 1\)

18.

Some equations involving \(x\) and \(y\) define \(y\) as a function of \(x\text{,}\) and others do not. For example, if \(x+y=1\text{,}\) we can solve for \(y\) and obtain \(y = 1-x\text{.}\) And we can then think of \(y = f(x) = 1-x\text{.}\) On the other hand, if we have the equation \(x=y^2\) then \(y\) is not a function of \(x\text{,}\) since for a given positive value of \(x\text{,}\) the value of \(y\) could equal \(\sqrt{x}\) or it could equal \(-\sqrt{x}\text{.}\) Select all of the following relations that make \(y\) a function of \(x\text{.}\) There are several correct answers.

\(y^6 + x = 1\)

\(y - \left|x\right| = 0\)

\(\left|y\right| - x = 0\)

\(y + x^2 = 1\)

\(4 x + 2 y + 4 = 0\)

\(y^3 + x^4 = 1\)

\(x+y=1\)

\(y^2 + x^2 = 1\)

On the other hand, some equations involving \(x\) and \(y\) define \(x\) as a function of \(y\) (the other way round).

Select all of the following relations that make \(x\) a function of \(y\text{.}\) There are several correct answers.

\(y^4 + x^5 = 1\)

\(y - \left|x\right| = 0\)

\(y^2 + x^2 = 1\)

\(\left|y\right| - x = 0\)

\(4 x + 2 y + 4 = 0\)