Lunch Stop -- Vernonia

We have lunch in beautiful downtown Vernonia. Many of us eat sitting on the curb in front of the Sentry grocery store across from the Post Office. I listen to three locals discussing this caravan of people who have invaded their street. One says he was told that these strangers are geology students. " Oh," says another, "they’re here to look at your kidney stones, Walter!" As they continue to chatter I watch them crane their necks to gawk at a couple of our more visually interesting members, students whose different colored hair and piercings become the topic of exotic speculation. Vernonia is a changed place now that we have passed through…

Stop #5 Pittsburg Bluff Formation

We try to compact our cars along a short length of wide shoulder on the downhill side of the highway. This is the more exciting aspect of these field trip along the Oregon highways. Trying to not get run over by traffic coming around a blind bend in the road as we cross to yet another road-cut. Here we find another sedimentary group buried beneath a veneer of weathered sands and loosely compacted concretions. There are conglomerates at the base with layers of crossbedded sandstone above them and mudstone layers higher up the face.

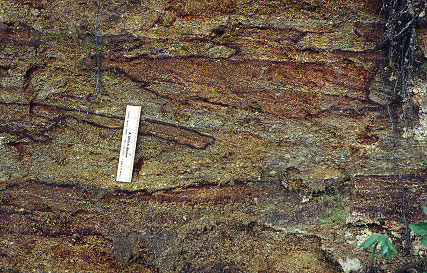

The cleaned face of the cut shows colored patterns of iron concretion in irregular patterns that seem more horizontal than vertical. The six-inch wooden ruler shows scale. Convoluted bedding indicates possible soil liquifaction from earthquakes. These sands are younger than the Keasey Formation. Melinda speculates that this was the delta or river bar, and because of the layering and grading, she guesses that this deposit might have been near an ocean. The convolutions indicate possible shaking while the sands were still quite soft and unconsolidated.

Stop #6

Another exposure of the Pittsburg Bluff Formation

We trek up the hillside through Devil's Club and along a dead electric fence to an old ranch or forest road. Somebody came through here with a D6 CAT ten or so years back and attempted to level a roadbed for some mysterious purpose, clear cutting, perhaps. About an eighth of a mile from the road we tromp into the middle of a 40 meter long cut that was dozed into the nose of a small ridge and lays open the subsurface about eight feet deep. At about shoulder level weather resistant blocks of a sandstone ledge hang over less resistant fine sandstone. Fascinatingly, at the bottom of this ledge lays a continuous layer of sea shells. It is the calcium carbonate from the shells that has cemented this layer of sand into a harder stone.

I work at trying to free a block of the ledge, but am forced to give it up because of time. So, lying on my back and focussing my camera up at the bottom of the ledge, I was able to get this photo of the “death bed” shells. It’s called that because one speculation suggests that this concentration of shells is due to some event that swept these animals from their beds and deposited them here, “graded out” in these sands, because they share a common density (and destiny) being lighter than gravels. Several marine critters can be identified among these fossil remains, (e.g. Cephalapods, bivalves, etc.).

These sands are not crossbedded and the laminar, finer material suggests a deeper water deposit than the previous Pittsburg Formation. Melinda explains how this could be a near-shore environment or along-side beach outside of the delta, river mouth.